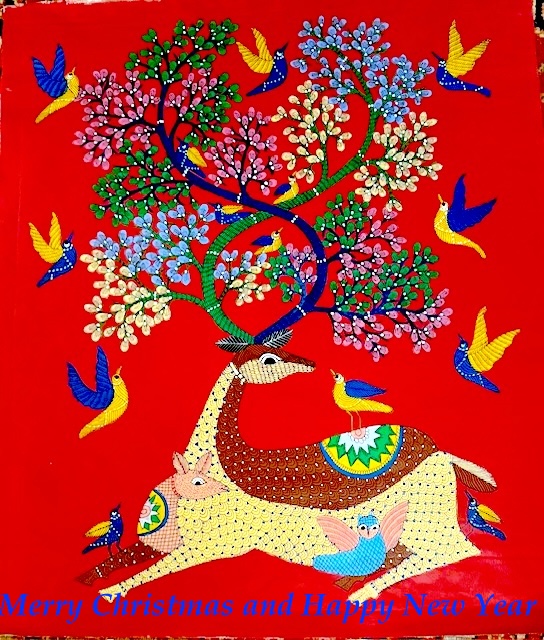

Theme of Hard Labour – birth, family and manual work

A rebel, like his grandfather, he started with graffiti then murals

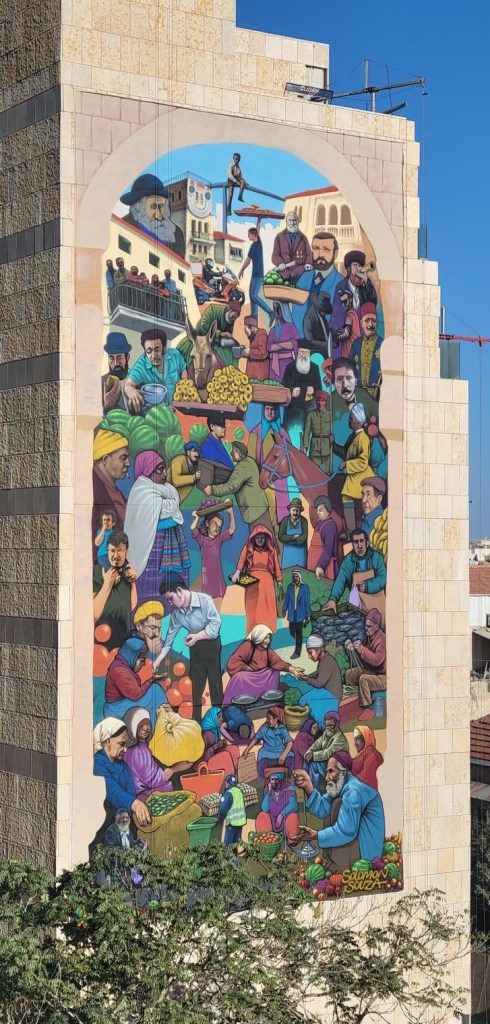

Solomon Souza paints fast. He had to he says when he began doing graffiti around the age of 12. “In the street you have to be fast, or you finish up in jail”. When he moved on to painting more acceptable wall murals, it was expensive hiring cranes, so speed was again important.

But there’s more to it than that. “Painting should be a burst of energy when you have an idea. It has to be done there and then,” Soloman told me while he was painting – in just three or four hours – a 12ft x 8ft mural (below) that is now hanging outside an exhibition of his work at the Cymroza Gallery in Mumbai.

“I love tackling large space and I rarely go back to change a work,” he said. “Your energy changes and you yourself change”.

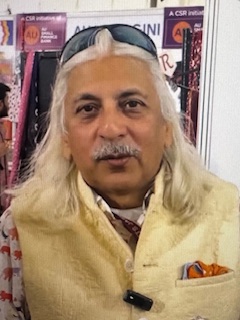

Age 32, energetic and an enthusiast who speaks quickly, Solomon is the grandson of F.N. Souza, one of India’s most famous masters and a leading member of the Mumbai-based Progressives group that included names such as Tyeb Mehta, M.F.Husain, and S.H.Raza.

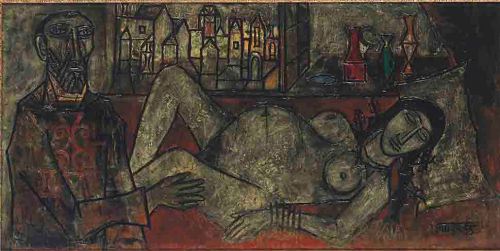

Souza’s 100th birth anniversary in 2024 is still being celebrated with exhibitions of his works including tortured and evocative canvases and line drawings of figures, often nude, and of townscapes, many with religious overtones.

Solomon says he always wanted to draw, or doodle, but he is known for huge murals that he has done from Israel to Goa. Cymroza’s is his first solo show for conventional paintings and is open till February 14. There are about 15 larger works with a variety of materials including oil, acrylic and poster paint on canvas and wood, and 50 smaller works on paper using oil bars, pastels and wax markers.

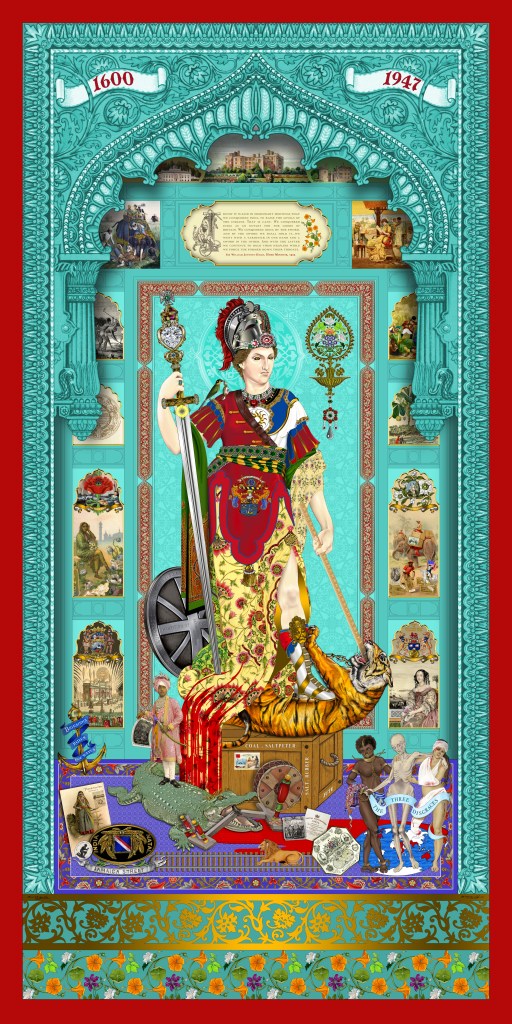

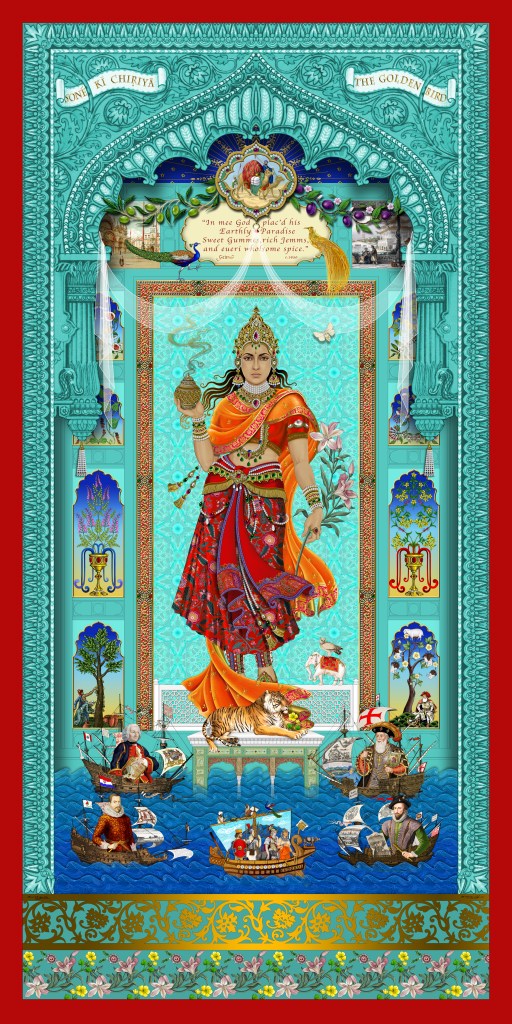

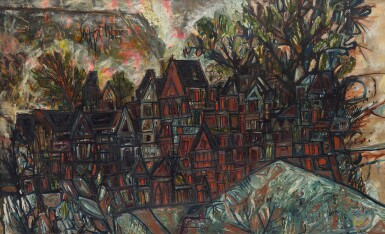

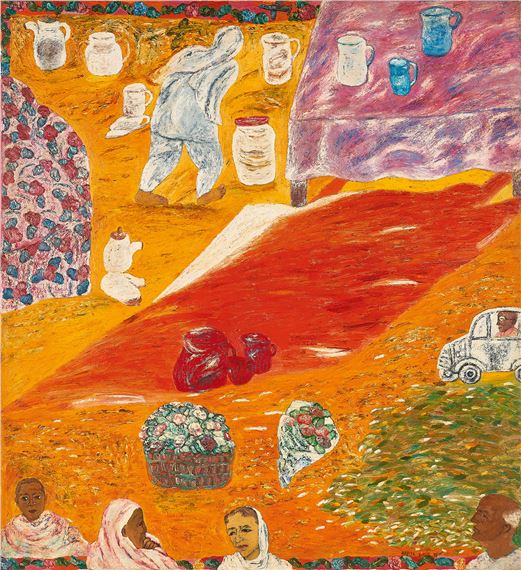

In some, he clearly has his grandfathers’ iconic works in mind, notably urban roof and cityscapes like the 12ft x 8ft mural, but the title of the exhibition is Hard Labour – “the working man and the labour of birth, building a family”, he says.

The focal point on entering the exhibition is a dramatically coloured work with that title (left), which combines the double theme with a naked woman who is pregnant and is labouring with a heavy mallet.

In an introduction to the exhibition, Solomon writes “Hard labour is all around us in myriad forms from the raising of a family to the building and maintenance of our cities and societies. Both are foundational in the fabric of existence…My first solo exhibition is about that hidden uncelebrated effort”.

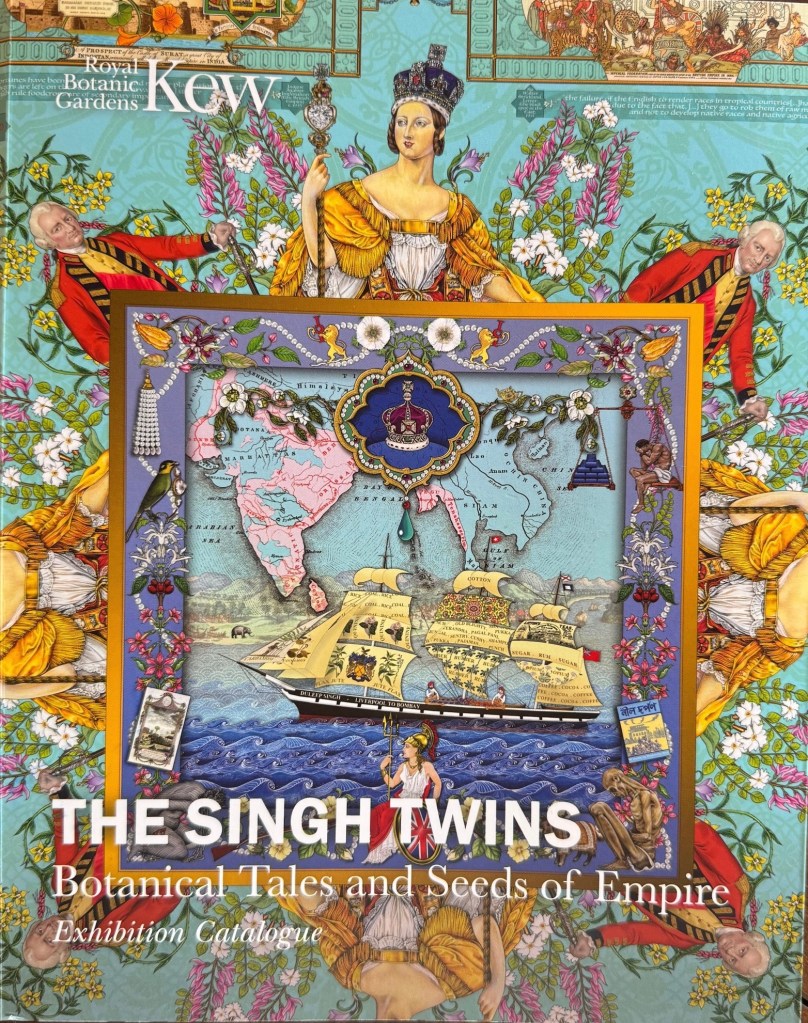

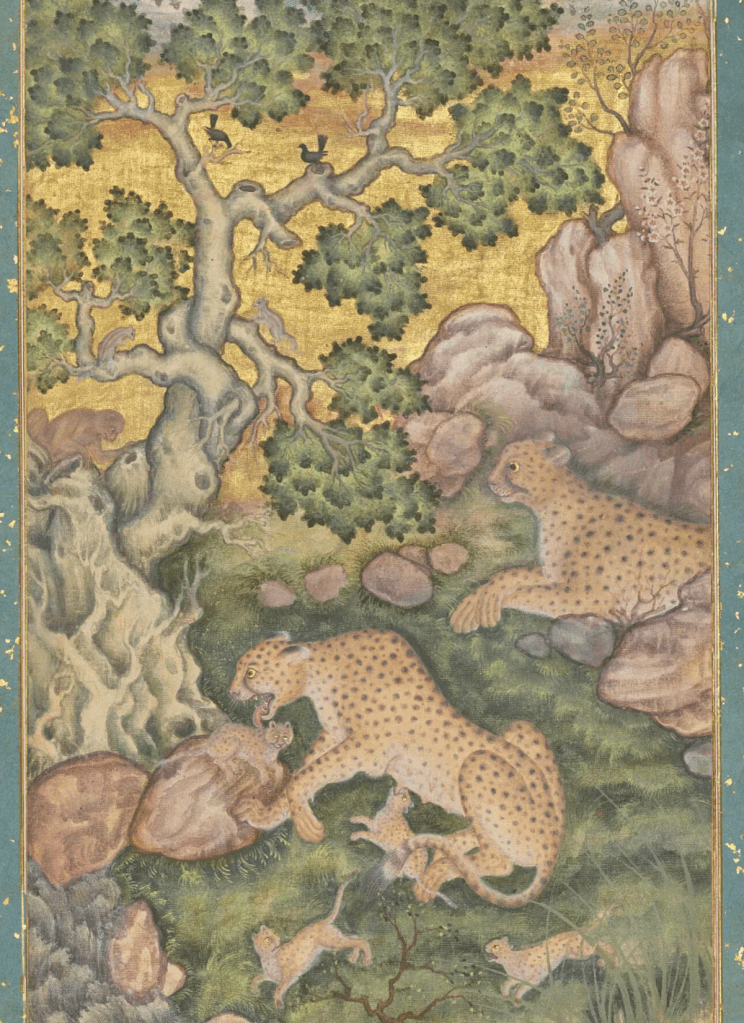

The largest work is Fruits of Labour, a 69in x 48in oil on canvas that he describes as a “tip of the hat” to his grandfather’s famous and visually similar Birth. Fruits of Labour (below) commemorates the birth of Solomon’s mother Keren, the daughter of F.N. Souza and his influential partner and muse Lisolette, a Czech-Jewish actress who fled from Prague to London in 1939.

Birth, painted in 1955 (below), portrays Lisolette pregnant with Keren, the first of their three daughters. It has set records twice for modern India art at Christie’s auctions – the sterling equivalent of$2.5m (including buyer’s premium) in London in June 2008 and $4.01m in New York in 2015. It is now in Delhi’s Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.

Next to Fruits of Labour is Life (below) that I felt had Buddhist overtones. It celebrates Solomon’s son’s birth and depicts him turning in the womb. Unlike all the other works, it is not, his wife has insisted, for sale.

“Solomon’s work has a unique freshness, showcasing a remarkable artistic talent for drawing,” says Pheroza Godrej who owns the gallery. “While portraying the themes of human birth and manual labour can be challenging, he has successfully accomplished this”.

Tough manual labouring features in many paintings, some seeming to echo the work of Krishen Khanna, 100, a close friend of F.N.Souza, and the only prominent surviving member of the Progressives.

Solomon says he didn’t realise the full impact of his lineage till he went with his mother in 2010 to a Christie’s auction in London. The squabbling family was selling many of his grandfather’s works in a massive auction of 152 lots. Almost all the lots sold, many doubling estimates with a total hammer price of £4.4m. (I was there and reported it here).

“I went in my school uniform. I didn’t really realise it was a sale of the estate, but the seriousness of the event was a big slap of reality, that all these fancily dressed people had come to see and buy my grandfather’s works,” says Solomon.

Keren took him when he was nine on what he describes as her “spiritual journey” to live in Israel where he grew up in her art studio. Graffiti with a spray can started when he was about 12 on his school walls in a town near Jerusalem. That was “in revenge for detention”. Sometimes he painted marijuana leaf, having “never touched it”.

In his teens, he was sent back to the UK for schooling. Living in Hackney in east London which was “saturated in graffiti”, he knew it was illegal but was rebellious like his grandfather so continued with “naming and tagging” what he painted.

“As I grew, my sense of adventure grew, and I found myself more and more frequently in trouble with the law, spending many nights in cells, with the burn of the handcuffs still sizzling upon my wrists,” he told Vivek Menezes, an art curator and festival organiser in Goa, who knew his grandfather in New York.

He returned to Jerusalem age 18 having failed his “O levels” in art because “I hadn’t done my homework. He wanted to go to art school in London, but Keren “begged him not to”, saying she could teach him art. “You don’t need to be told what you are,” she said.

Back in Jerusalem, his views on graffiti changed. “I felt it was a beautiful holy place, and I shouldn’t do graffiti”. He turned to murals and street art, “trying to add value”.

He became famous for spray painting some 300 works over two years on the shutters of stalls in the Mahane Yehuda (Camp of Judah) market. “The souk had seen a lot of violence and hadn’t recovered; there was a sadness and people avoided the area. So, we painted portraits of people who worked there on the shutters, then bars opened and it became a bustling centre”.

Menezes persuaded Solomon to move to Goa in 2019 and paint what has become a total of 20 murals including the side of a five-storey building (above) that was done in one day. In 2020 he even went stadium-scale in London for the Chelsea Football Club.

He feels at home in Goa with his wife and children though, he says, “I regard myself as Jewish and my heart is in Jerusalem”. He painted most of the exhibition’s works in India where he says he “found a new spark”.

I watched his energy for two hours or so at the Cymroza in the Breach Candy area of Mumbai when he was painting the large 12ft x 8ft board with poster paint using rollers and small spray guns. “His work has been highly acclaimed for its daring style, technical proficiency, and influence on culture, especially in wall art – mural painting, such as the piece he created at the entrance of Cymroza Art Gallery,” says Pheroza Godrej.

When I arrived, he had completed the basic buildings of the Mumbai urban roofscape on a black background. “I like painting on black and enjoy how the colours jump out. You lose that vibrancy with a white background,” he said as he filled the black sky with short strokes creating a blueish whitish stream.

Next, he strengthened the outline of the buildings and roofs with sprayed black lines, then blue spaces for windows, images of trees on prepared background and finally yellow for lights and more splashes of colour till finally the city scape was complete.

There was a lot of his grandfather in the concept and the detail, but it was clearly Solomon’s inspiration, all completed in three to four hours. And he enjoyed it, which he said was important, and that sounded different and happier than his grandfather’s compulsions.

Declaration of interest: I bought two small paper works

Recent Comments